Technodiversity glossary is a result of the ERASMUS+ project No. 2021-1-DE01-KA220-HED-000032038.

The glossary is linked with the project results of Technodiversity. It has been developed by

Jörn Erler, TU Dresden, Germany (project leader); Clara Bade, TU Dresden, Germany; Mariusz Bembenek, PULS Poznan, Poland; Stelian Alexandru Borz, UNITV Brasov, Romania; Andreja Duka, UNIZG Zagreb, Croatia; Ola Lindroos, SLU Umeå, Sweden; Mikael Lundbäck, SLU Umeå, Sweden; Natascia Magagnotti, CNR Florence, Italy; Piotr Mederski, PULS Poznan, Poland; Nathalie Mionetto, FCBA Champs sur Marne, France; Marco Simonetti, CNR Rome, Italy; Raffaele Spinelli, CNR Florence, Italy; Karl Stampfer, BOKU Vienna, Austria.

The project-time was from November 2021 until March 2024.

Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

A |

|---|

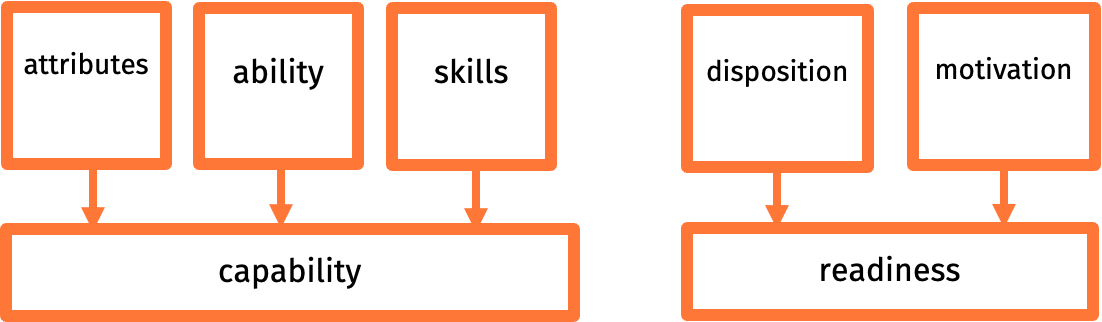

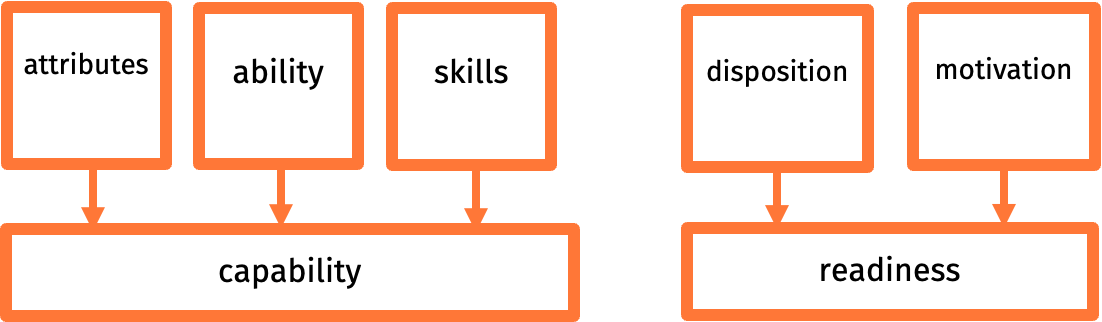

Abilities of a workerErgonomics follows a very simple basic model that derives from physics: When you impact a body with a certain stress, the body will react with a corresponding strain. Since a standard method causes a stress that is typical for this standard method, the strain as a reaction to this typical stress situation should be typical, too. The intensity of the strain, however, is not the same. It depends on the worker: his personal attributes, his abilities and his skills (together they form the capability for work). And it varies due to the actual disposition and motivation (together called readiness for work), and his health. If the strain overruns the permanent work load, breaks are necessary for his personal recovery to avoid acute or chronic damage. Every worker has his individual abilities and strengths. The same job that is easy for somebody can be difficult for another person; we say that the first person is more talented for this job than the other one. (See more under TDiv PR1-E04)  | |

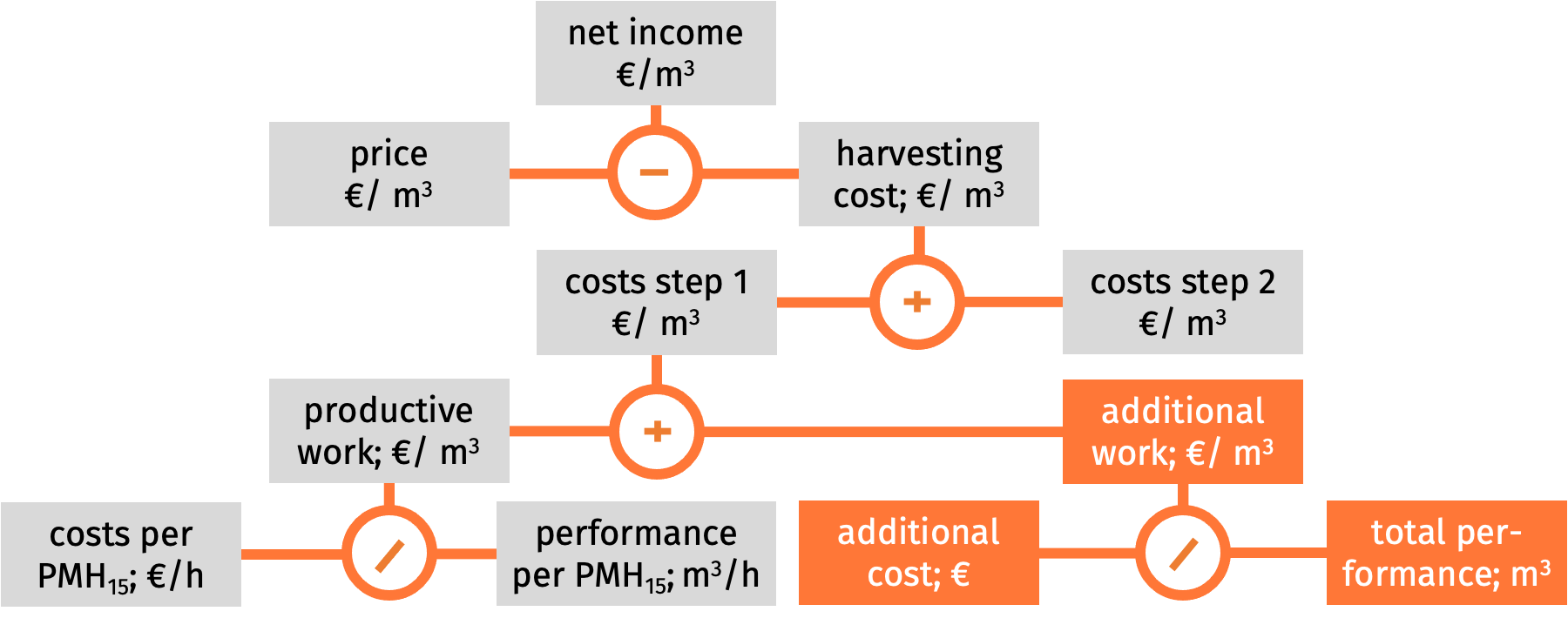

Additional costsAdditional costs are a part of the cost calculation. They occur when the work is necessary for the production, but is not productive in a sense that there is an output of any products. Very often it happens that workers are working hard, but do not produce any single product. As an extreme example, take the work with a cable yarder. Before the yarder can be installed, an engineer must explore the terrain and trace a ground profile with distance and inclination. Based on that profile, he can select the best path for the cable corridor, selecting suitable spar trees, anchors and intermediate supports. Then he’ll go back to the forest and mark the corridor. Now a troop of specialists installs the yarding system. The end-mast and the intermediate supports must be prepared: they are stabilized with guylines, some pulleys are fixed, saddles are mounted… Finally, the skyline is laid out, lifted and tightened. This takes the work of several persons and the basic machine over hours. Now the productive work begins. When all logs in the area have been extracted, the yarder system needs to be dismantled. Also here, a troop of persons takes down the skyline, frees the end-mast and the intermediate supports, collects all materials (cables, pulleys, strops etc.) and stores all, ready for transport to the next site. All these additional costs must be regarded when the costs per m3 are calculated. With yarder systems, they can be so high that the extraction with yarders will be achievable only under conditions of small clear-cuts. (See more at TDiv PR1-C04)  | |

Advanced mechanized workThe term mechanized work describes the degree of mechanization of a technical operation. Other degrees are manual work and motor-manual work. Mechanized work can further be divided into simple, advanced and automatic work. When the machine takes over the auxiliary function to handle the object with means of a crane or a grapple, e.g., we call it advanced mechanized work. A typical example is a tractor or forwarder equipped with a loader. In this case the driver can control all important functions of the system without “feet on the ground or hand on the tree” (Lövgren, Swedish scientist). Given the hazards of forest work, this can be an important improvement in terms of safety and ergonomics – not just production efficiency.   | |

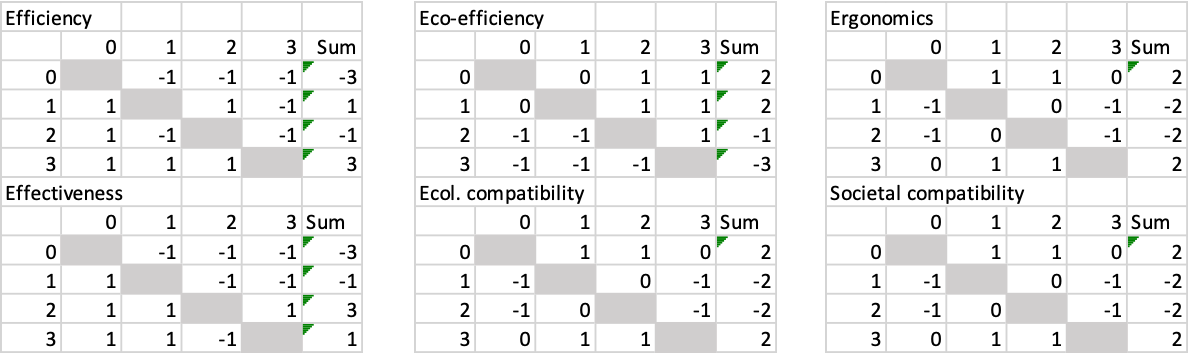

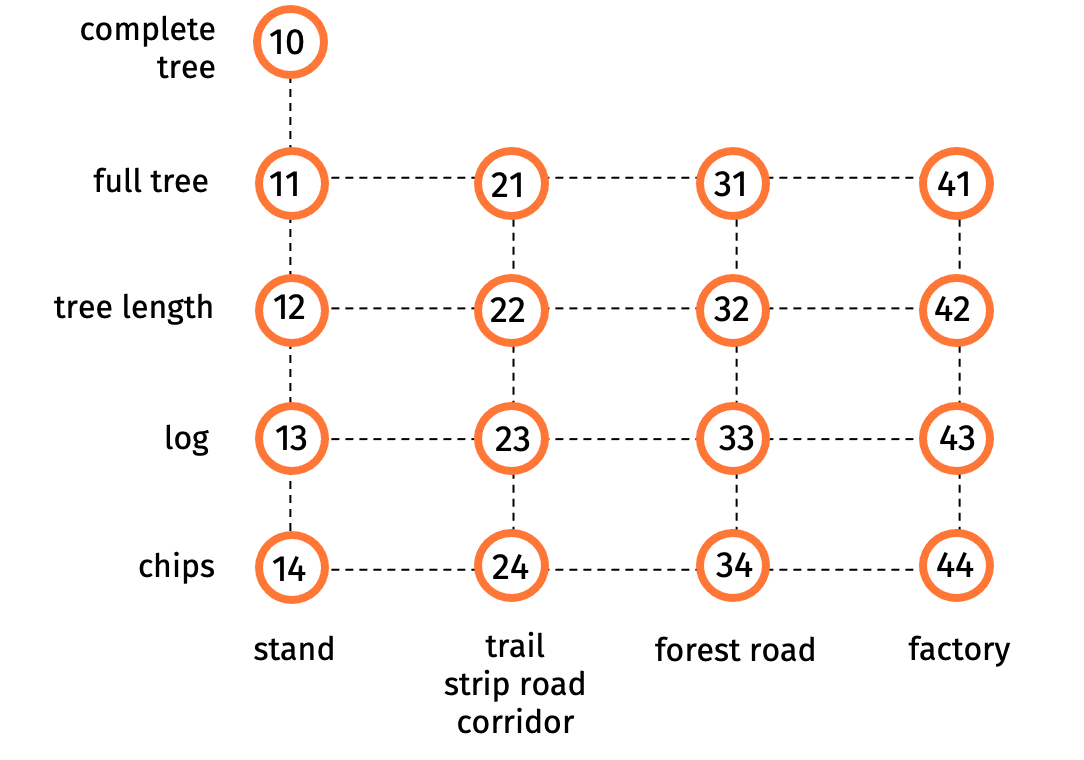

AHPThis is one method to find the best option. Other methods are minimax rule, monetarization, utility analysis, and optimality curves, for example. In 1990 Saaty proposed a new solution based on paired comparisons. Under each criterion we ask which one of two options is better. At the end we count the relations of the options. The option with the highest sum of “wins” is the best. Using the same example as with the other methods, we can come to following tables:

With so few options it is easy to find the relations and to calculate the “wins”. In fact, Saaty’s method is more sophisticated than just that, but for us it is enough to use the same weights as before. We see, that under this method the advantage of option 3 is more visible. All other options are comparably bad. This is a result that can be seen often: the method tends to exaggerate relationships because it does not discriminate between small and large differences. AHP is widely used in sciences – but only there. For practice life it covers too many hidden effects.

(See more at PR1-F04) | |

Almost fully mechanized method | |

Attributes of a workerErgonomics follows a very simple basic model that derives from physics: When you impact a body with a certain stress, the body will react with a corresponding strain. Since a standard method causes a stress that is typical for this standard method, the strain as a reaction to this typical stress situation should be typical, too. The intensity of the strain, however, is not the same. It depends on the worker: his personal attributes, his abilities and his skills (together they form the capability for work). And it varies due to the actual disposition and motivation (together called readiness for work), and his health. If the strain overruns the permanent work load, breaks are necessary for his personal recovery to avoid acute or chronic damage. The attributes of workers are different like gender, age, height, weight, power… In practical life, these attributes are regarded to be invariable. (See more under TDiv PR1-E04)  | |

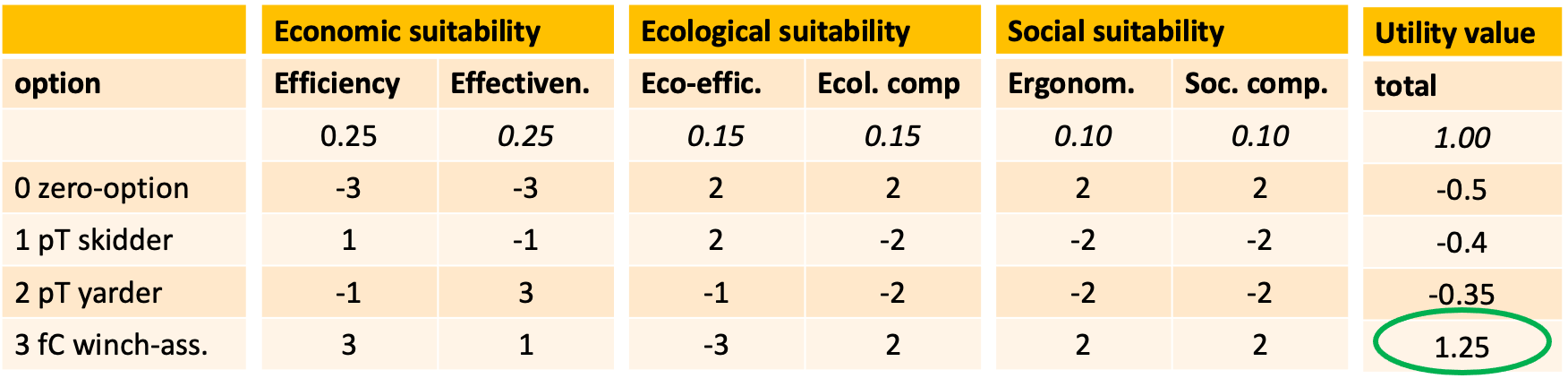

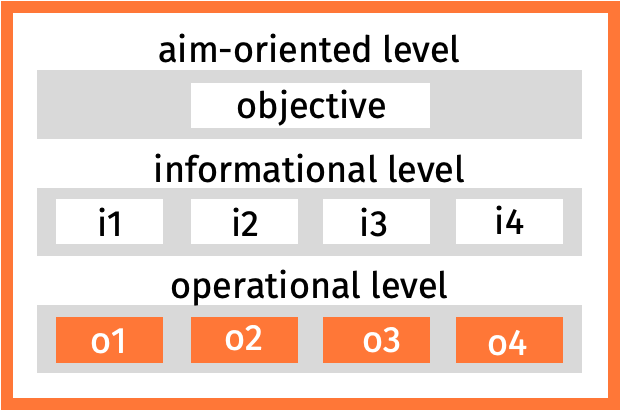

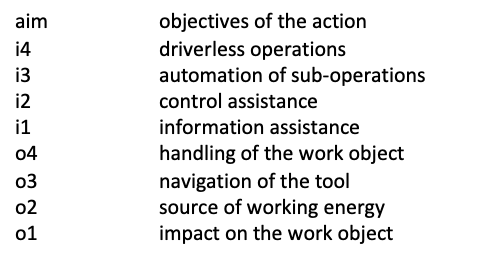

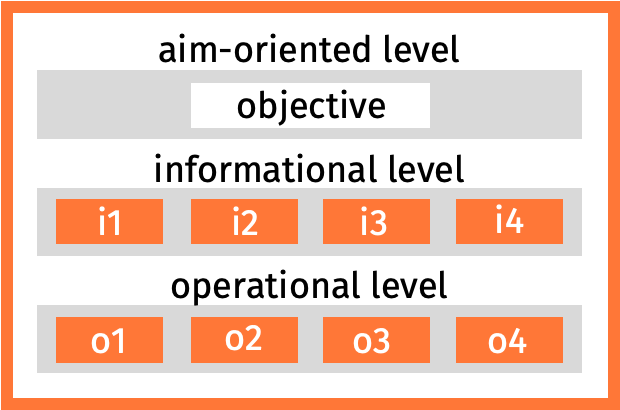

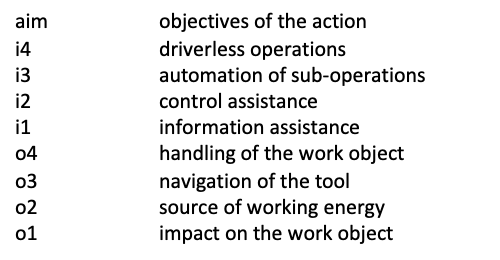

Automatic workThe term mechanized work describes the degree of mechanization of a technical operation. Other degrees are manual work and motor-manual work. Mechanized work can further be divided into simple, advanced and automatic work. Automatic work can be subdivided into different degrees of automation.: •i1

information assistance (by sensors)

•i2

control assistance (by electrohydraulic control, e.g.)

•i3

automation of sub-processes

•i4

driverless operations In forestry, the cut-to-length harvester is an example for a machine with partly automatic work (at level i3). Some prototypes try to operate driverless (i4).   | |

AxeAn axe is a tool used for the cutting of objects. It is composed of a shaft and a steel wedge, which is sharpened on the narrow side. The axe is one of the oldest tools used for felling trees (buffer 10 to 11). Furthermore, it can be exploited for delimbing (buffer 11 to 12) and wood splitting (buffer 12 to 13). Because human force is needed to cut with an axe, the work with an axe is assigned to the manual work. Other harvesting tools, the use of which is assigned to manual work, are the machete, the bush knife, and the hand saw. (See PR1-B03)

| |

B |

|---|

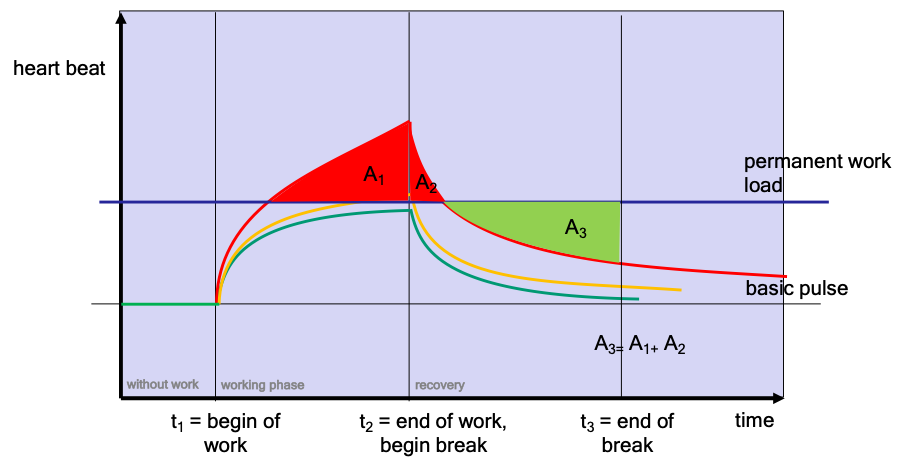

Breaks during the workIf the strain of a worker overruns the permanent work load, it may increase the danger of an acute or chronic damage. Therefor breaks for recovery are necessary and should actively be provided by the employer. The minimal duration of this break should correspond with the strain over the permanent work load to bring enough compensation to the overrunning strain. We call it “shortest break”, because it should not be shorter than the given duration in order to fulfil its requirement. In the figure below, we have three working situations: - The green line shows a work, where the strain (here indicated with the heart beat) during the working time does not run over the permanent work load. So, the shortest break is zero, no compensation is required. - With the yellow line, the permanent work load is reached but not overrun. Also here, we don’t need any break. - At the red line, the heart beat is for a long time over the permanent work load. Here a debit increases that needs to be compensated. This debit can be interpreted by the area A1. In the first seconds of the break the heart beats are higher than the permanent work load; so, though they are decreasing, the heart beats (A2) are counted as overrunning strain, too. The break is long enough, when the area A3 between heart beats and permanent work load is as large as the sum of A1 and A2. Now the compensating effect is enough. There are three other types of breaks that have other effects: - organic breaks allow some organs to be unloaded while the load is taken over by other organs; one example is to move a heavy load from one hand into the other hand - short breaks of five minutes are for personal belongings and to recover the mind from concentration - longer breaks with 15 to 30 minutes allow to take lunch and to communicate with other colleagues (See more under TDiv PR1-E04)  | |

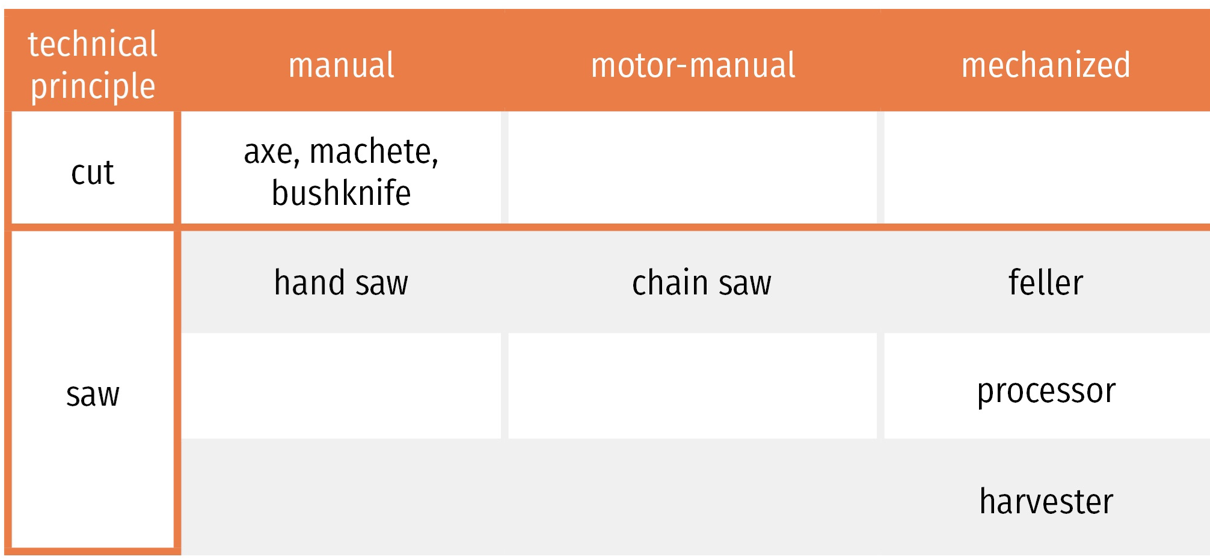

BufferA term that is often used in system analysis. A buffer interrupts a flow and opens a space for contents that can be stored and loaded again. It is the link between two elements in a chain. In Technodiversity, we take this concept to describe interruptions in a harvesting process, which divide the process into two sub-processes. Since the buffer allows to store the logs, the connected sub-processes must not wait one for each other and can develop their full productivities. In the functiogram, the buffers are represented by a button while the cub-processes are shown by arrows. In order to concatenate the sub-processes, they must meet at a buffer. So, the buffers have a key role for building and optimizing harvesting processes. In lecture PR1-B07 they are named by numbers. (See PR1-B07)

| |