Technodiversity glossary is a result of the ERASMUS+ project No. 2021-1-DE01-KA220-HED-000032038.

The glossary is linked with the project results of Technodiversity. It has been developed by

Jörn Erler, TU Dresden, Germany (project leader); Clara Bade, TU Dresden, Germany; Mariusz Bembenek, PULS Poznan, Poland; Stelian Alexandru Borz, UNITV Brasov, Romania; Andreja Duka, UNIZG Zagreb, Croatia; Ola Lindroos, SLU Umeå, Sweden; Mikael Lundbäck, SLU Umeå, Sweden; Natascia Magagnotti, CNR Florence, Italy; Piotr Mederski, PULS Poznan, Poland; Nathalie Mionetto, FCBA Champs sur Marne, France; Marco Simonetti, CNR Rome, Italy; Raffaele Spinelli, CNR Florence, Italy; Karl Stampfer, BOKU Vienna, Austria.

The project-time was from November 2021 until March 2024.

Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

R |

|---|

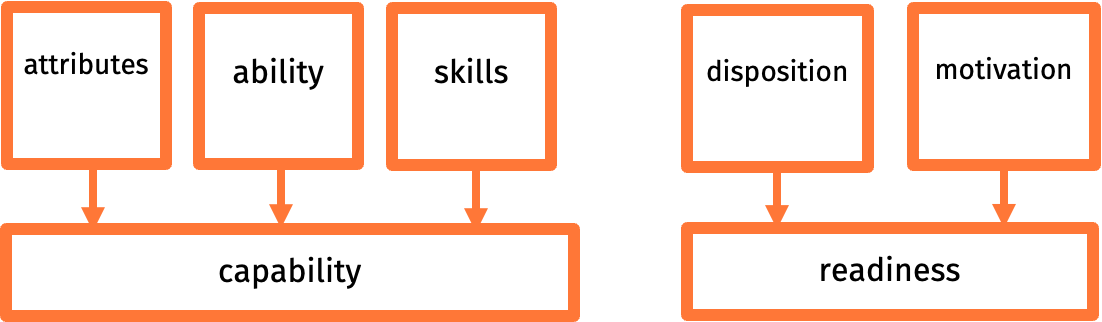

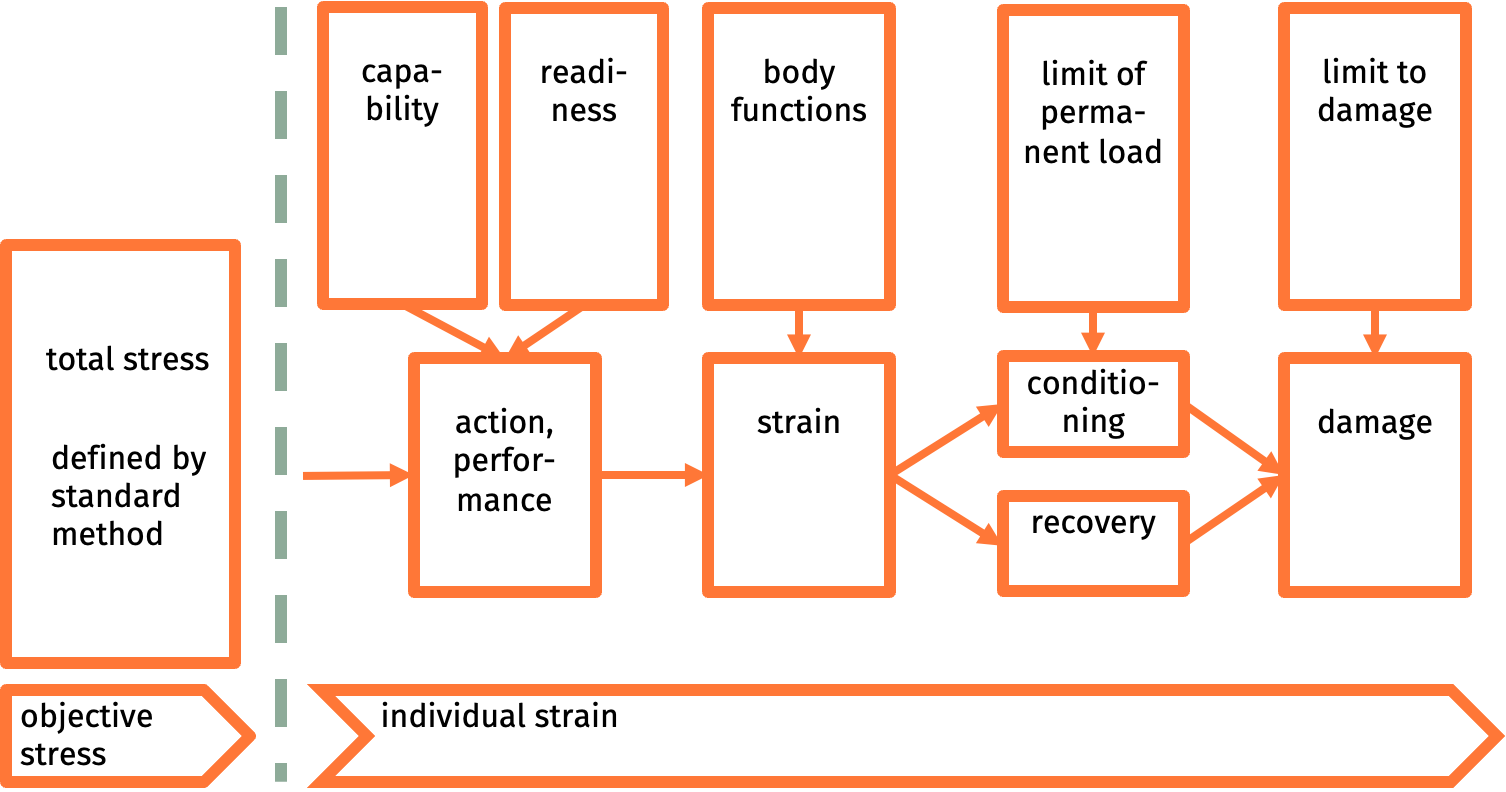

Readiness for workErgonomics follows a very simple basic model that derives from physics: When you impact a body with a certain stress, the body will react with a corresponding strain. Since a standard method causes a stress that is typical for this standard method, the strain as a reaction to this typical stress situation should be typical, too. The intensity of the strain, however, is not the same. It depends on the worker: his personal attributes, his abilities and his skills (together they form the capability for work). And it varies due to the actual disposition and motivation (together called readiness for work), and his health. If the strain overruns the permanent work load, breaks are necessary for his personal recovery to avoid acute or chronic damage. We know that there are days when the same job feels hard, and days when it feels much easier. This depends on the disposition (physical variance) on one hand and the motivation (mental variance) on the other hand. Both together form the readiness for work. While capability is the potential of any given person, readiness is the percentage of that potential actually activated. (See more under TDiv PR1-E04)

| |

RecoveryErgonomics follows a very simple basic model that derives from physics: When you impact a body with a certain stress, the body will react with a corresponding strain. Since a standard method causes a stress that is typical for this standard method, the strain as a reaction to this typical stress situation should be typical, too. The intensity of the strain, however, is not the same. It depends on the worker: his personal attributes, his abilities and his skills (together they form the capability for work). And it varies due to the actual disposition and motivation (together called readiness for work), and his health. If the strain overruns the permanent work load, it may have two consequences: On one hand the body is pushed to improve its capacities. We use this effect for active training and conditioning. But on the other hand, acute or chronic damage can occur. Therefor breaks for recovery are necessary and should actively be provided by the employer. (See more under TDiv PR1-E04)  | |

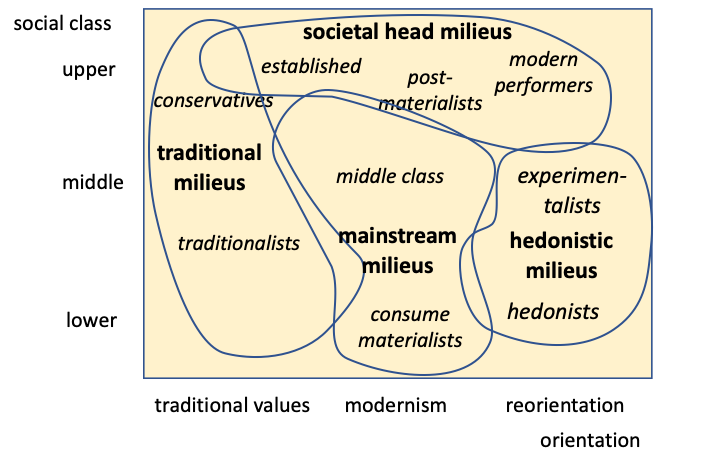

RecreationOne aspect of societal compatibility is the potential to get in conflict with people who seek recreation in the forests. This group of forest users is not homogenous and so their demands are diverse, too. This makes it difficult to fully meet their needs. Some studies have tried to describe this population of forest users. As an example, we can quote the research work of Kleinhückelkotten, who correlated forest visitor’s characteristics with SINUS-milieus that are widely used in socio-economics. SINUS-milieus try to categorize people based on the intersection of social class (defined by income as lower or upper class) and the main orientation like traditional values, believe in modernization or reorientation and experimentation as shown in the figure. Though these results are only representative for Germany at beginning of this century and cannot be transferred to other countries without adaptations, the basic information seems to be relevant in general. The groups are: · 22% holistic forest friends · 16% ecological forest romantics · 23% pragmatical distant persons · 22% self-centered forest users · 18% indifferent persons. But all forest visitors have one common need: they use the forest roads as their access to the forest and don’t want to be disturbed. consequently, if we keep the roads clear for people to move on them, this can help to improve the acceptance of forest techniques and operations. In Technodiversity, we have invented the S-class that describes the grade of disturbance on the forest road by harvesting operations. (See more

under TDiv PR1-E02)  Lit.: Kleinhückelkotten S., Calmbach M., Glahe H.-P., Stöcker R., Wippermann C. & Wippermann K. 2009: Kommunikation für eine nachhaltige Waldwirtschaft. Forschungsverband Mensch & Wald, M&W –Bericht 09/01, Hannover, S. 33 ff | |

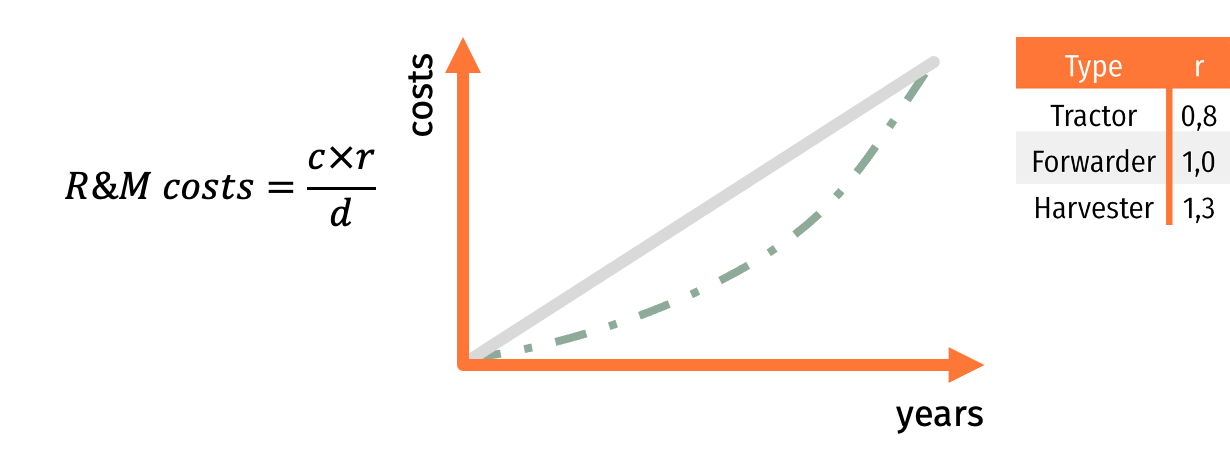

Repair and maintenance costsRepair and maintenance (R&M) costs are a part of the cost calculation with the engineering formula. They consider the estimated costs for repairs and services during the life span of the machine. Saving money in anticipation of breakdowns and regular planned maintenance has two effects:Have money available when maintenance is needed and to share those costs that occur irregularly with all customers. From other machines we can get a feeling of how high the R&M costs would be. As a general rule of thumb based on experience, a forwarder needs the same sum for repairs and maintenance over its whole service life span as the initial price of the machine. A tractor takes a bit less, a harvester a bit more. This relationship can be expressed as a factor “r” for repairs. Now it’s easy to calculate the costs of repair and maintenance: • Take the price of initial investment • multiply it with factor r • and divide it by the number of years that you expect the machine to run. However, the trend is not linear. Normally, a machine will have very low R&M costs in the first years, then those costs will increase as the effect of wear develops. Therefore, this calculation accounts for the average costs per year over the whole machine lifetime. Old machines that are written-off and don't cost for depreciation or interest, have a wide space for R&M costs. This is the reason that there is a market for written-off machines. (See more at TDiv PR1-C02)  | |

Resilience of soilSee natural regeneration of soil | |

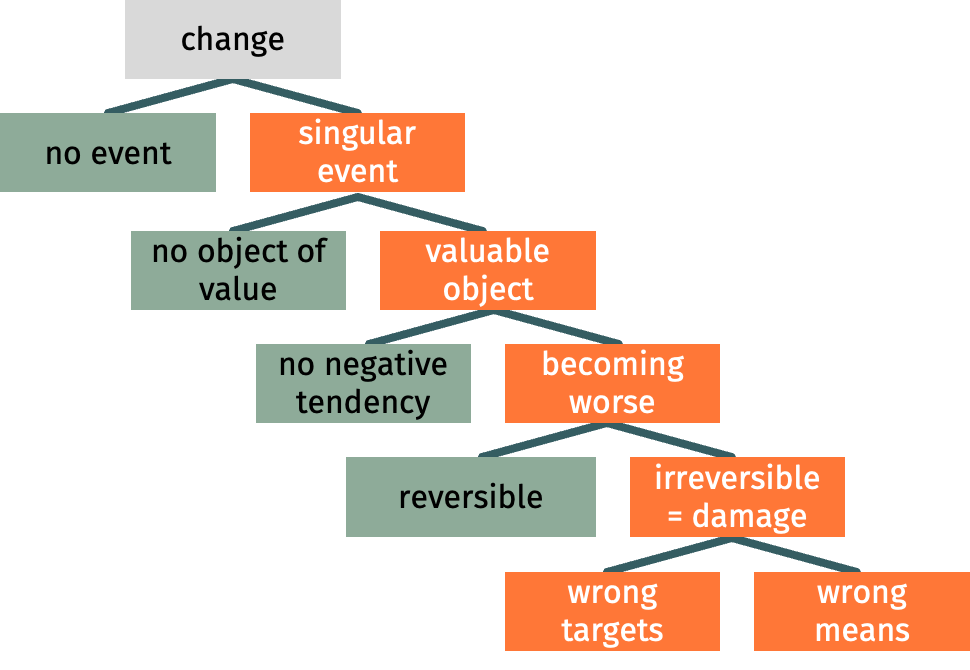

Risks and side-effectsRisks and side-effects are non-intended effects of our actions. Side-effects happen, whether we like it or not. Normally this term is preferred for those that hurt us, not for the indifferent or desired ones. The task is to find a way to keep those undesirable side-effects within acceptable limits. To that end, we must improve our system or run a new system selection. Contrary to side effects, risks may happen but are not inevitable. If they happen, they often cause heavy damage. If, e.g., we a damage that will cost 1000 € - if it happens. If we estimate that this damage will occur in 5 % of all cases, the risk is 1000 € x 0,05 = 50 €. But be careful with the word damage, because not every change is a damage. To category any result as a damage is an anthropocentric decision: To be a damage, the change must be is caused by a singular incident, that we can undoubtedly address. But not all changes disturb the needs of human beings. So, the decision to be a damage is an anthropocentric one. A damage only happens to things that have a certain value for us. This may not be expressed in terms of money: it can also be ecological value, social value or emotional value… the fundamental thing is that value is being lost. And of course, only those consequences that are not desirable from the human point of view are a damage. The system, will it be able to reverse it in a reasonable time? If so, we can accept it. But if not, it really is a damage. But what is a reasonable time? In Technodiversity, as a practical approach we have defined reasonable time as the time span between two interventions – like “return time”. For example, for thinning operations 5-10 years, for systems with permanent cover (tropics) 25-40 years. If recovery needs longer than that time span, we may consider the damage as permanent. When we want to know who is responsible for a damage, we should be careful. In forestry, very often people have the tendency to blame the machines if something goes wrong, because they look strange and aggressive in the nature. But a lot of negative changes have their root cause in a wrong decision. In such case, the machine is not to blame, but the manager, who has taken the decision. But in the case that the machine has caused the damage, we should address it clearly to avoid the same incident in the future. Damage by forest operations is sub-divided into felling damage and skidding damage. (See more at PR1-D01) | |

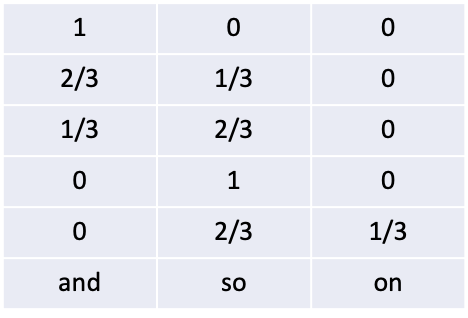

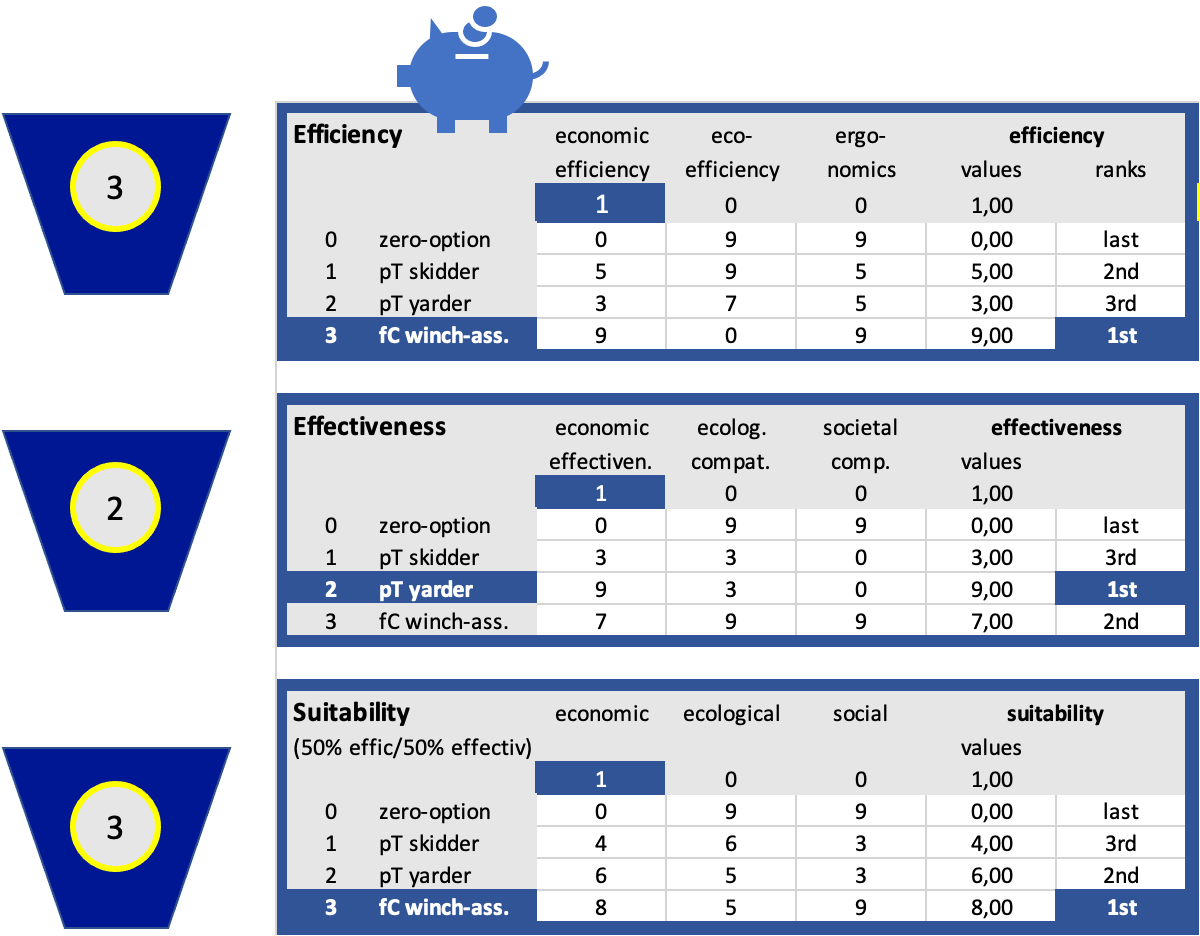

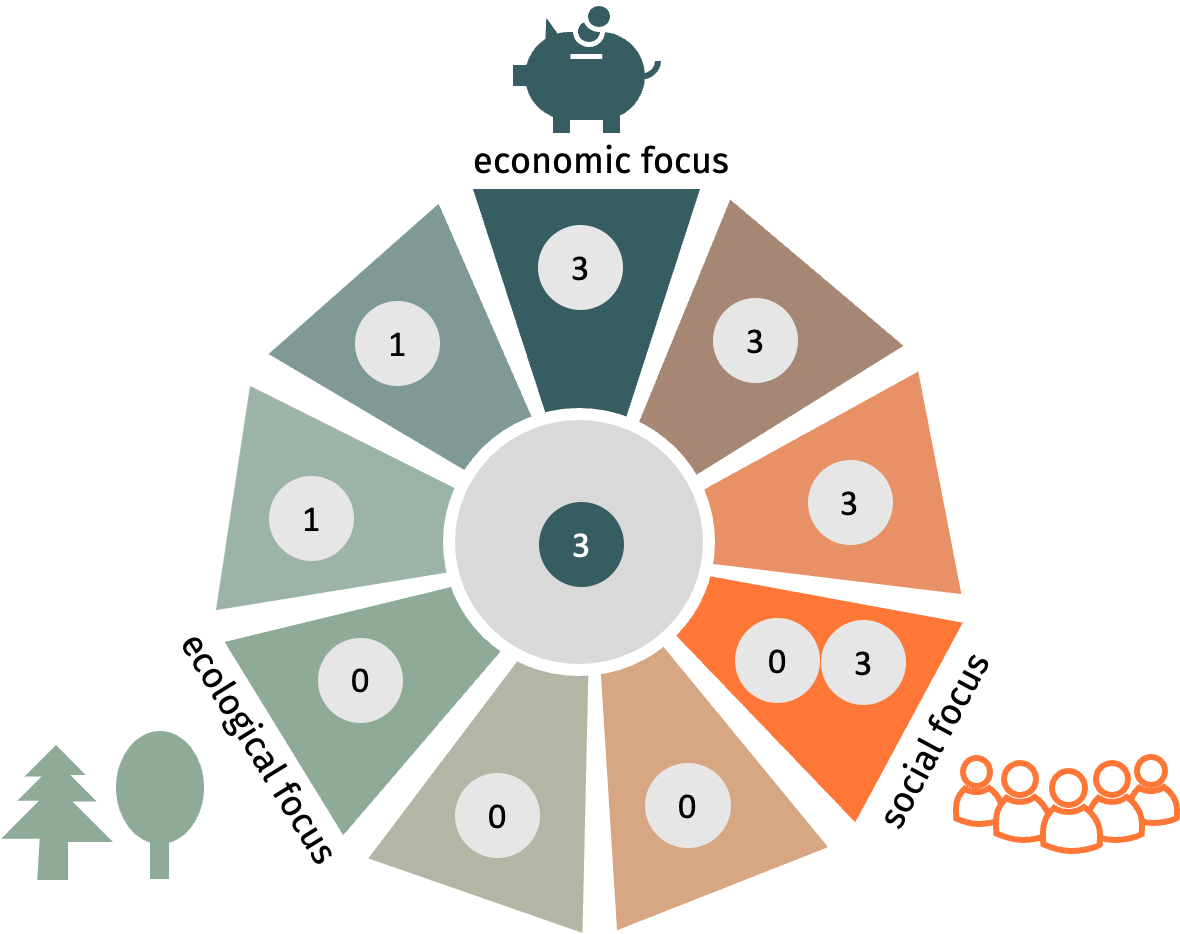

RosetteFor decision making, we have several methods to find the best option. Examples are minimax rule, monetarization, utility analysis, AHP, and optimality curves (see PR1-F04). They all have in common that the decision is generally made in order to achieve a specific goal. But unfortunately, in real life the goal is not always clear. Therefore, with the rosette the argumentations is turned from head to feet: We ask which option will be the best when we modify the goal. As an example, we take the same example as with the other decision making methods with the same “scores” as well. And – like with school grades – we accept to treat them like cardinal numbers. That way we can use the mathematical operations of addition and multiplication. Then we play with weighing in order to clarify the effect of changing priorities on option ranking. When we take economy as the sole criterion (100% weight), we get the following optima:

If we select ecology as the sole criterion (100% weight), we get the following optima:

And finally, if we choose social aspects as the sole criterion (100% weight), we get the following optima:

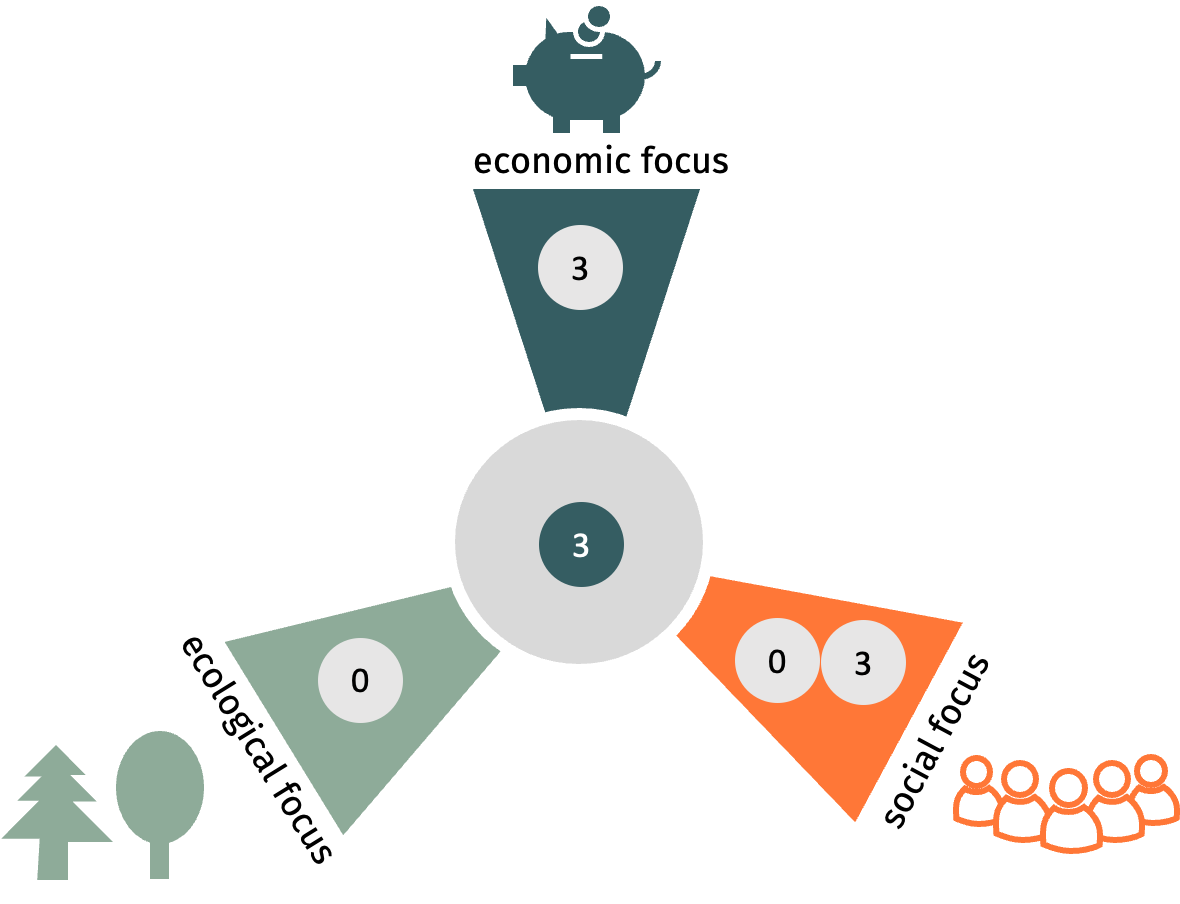

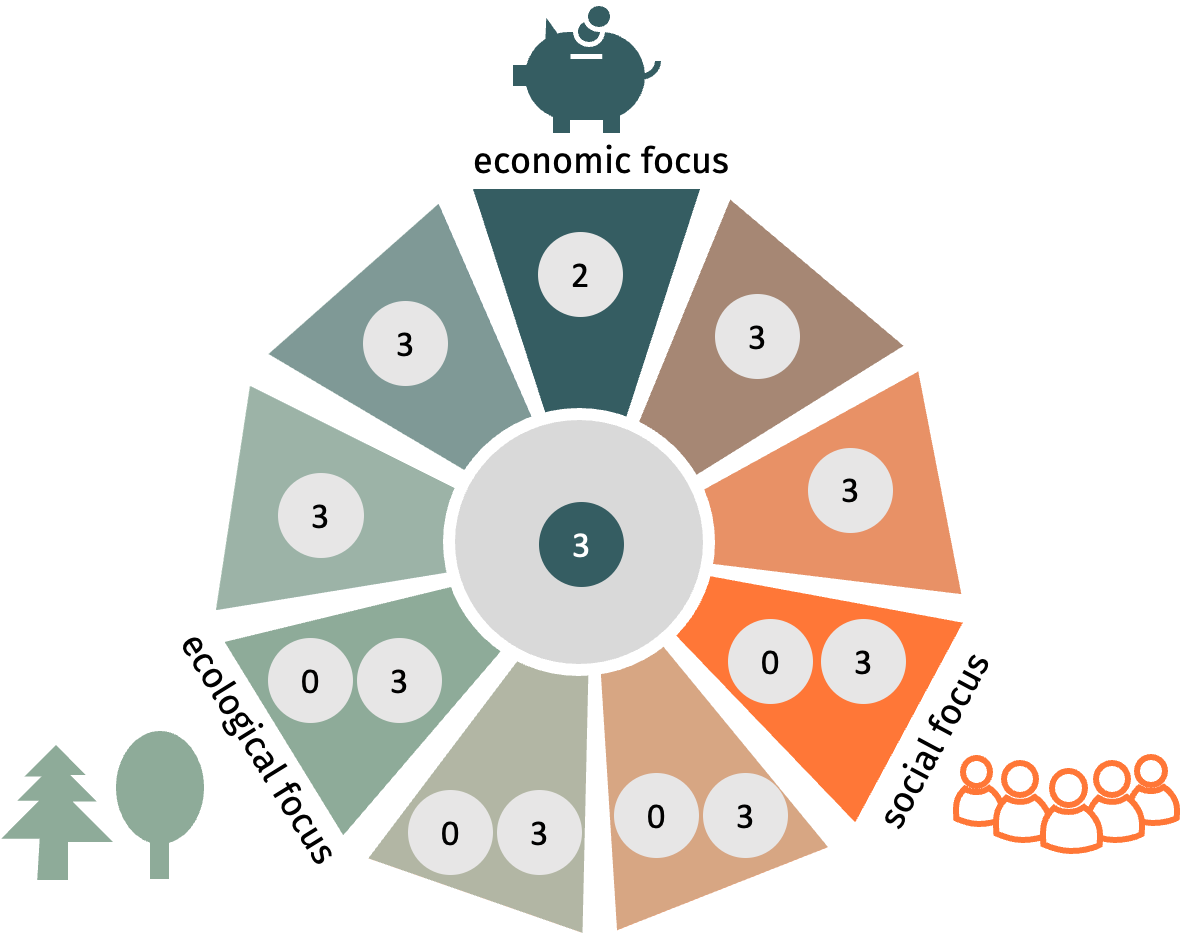

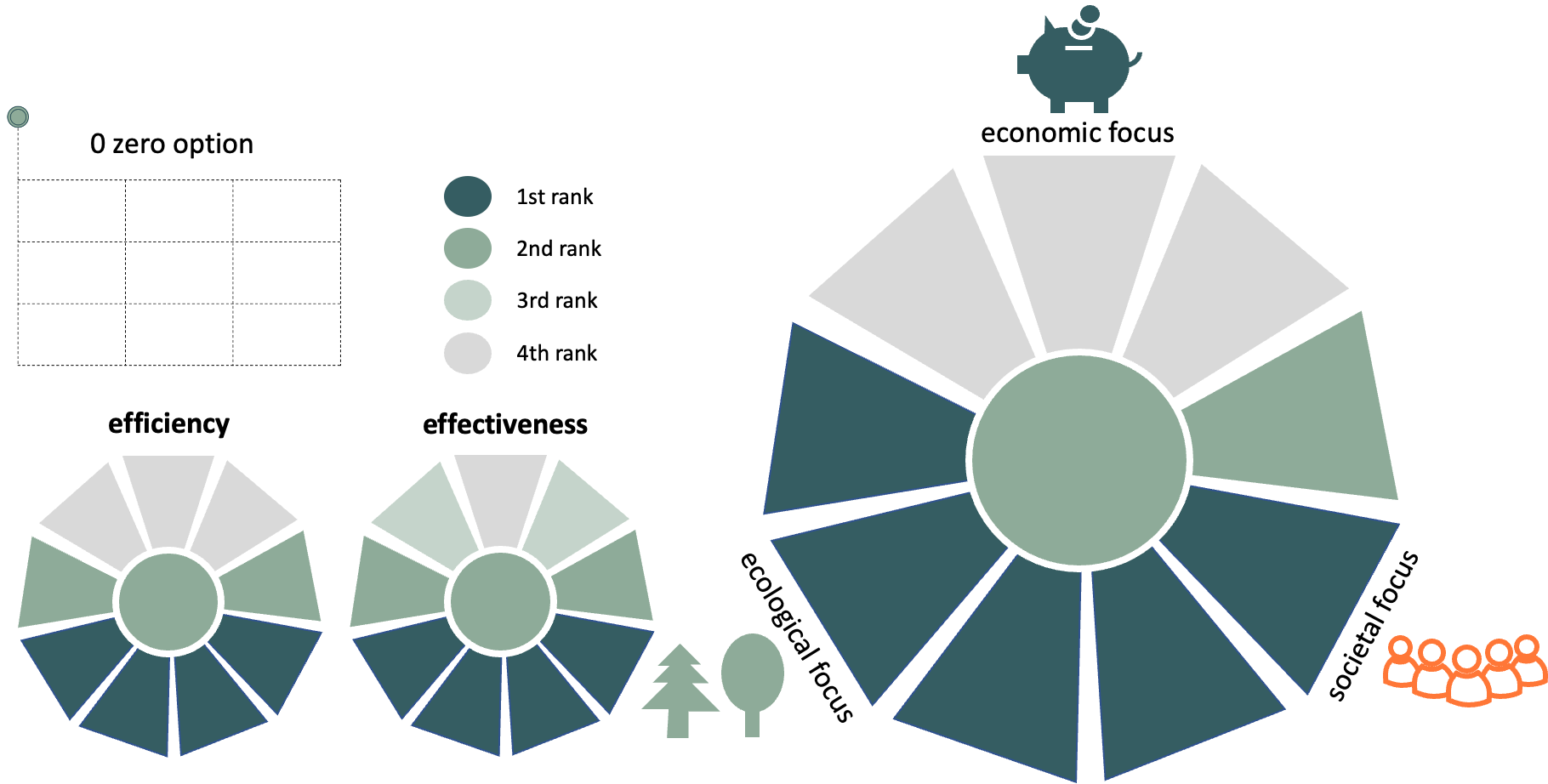

Until now, it seems confusing. But by introducing some finer transitions, hopefully we shall find a pattern. We will calculate these transitions with the weights: When we paint all 10 combinations and arrange them to a "rosette", we can put our winners the three poles:

We can make it separately for the effectiveness and the efficiency or as combination of both for the suitability (like above). Here we see the result of the example for all aspects: Under efficiency aspects

Under point of view of effectiveness

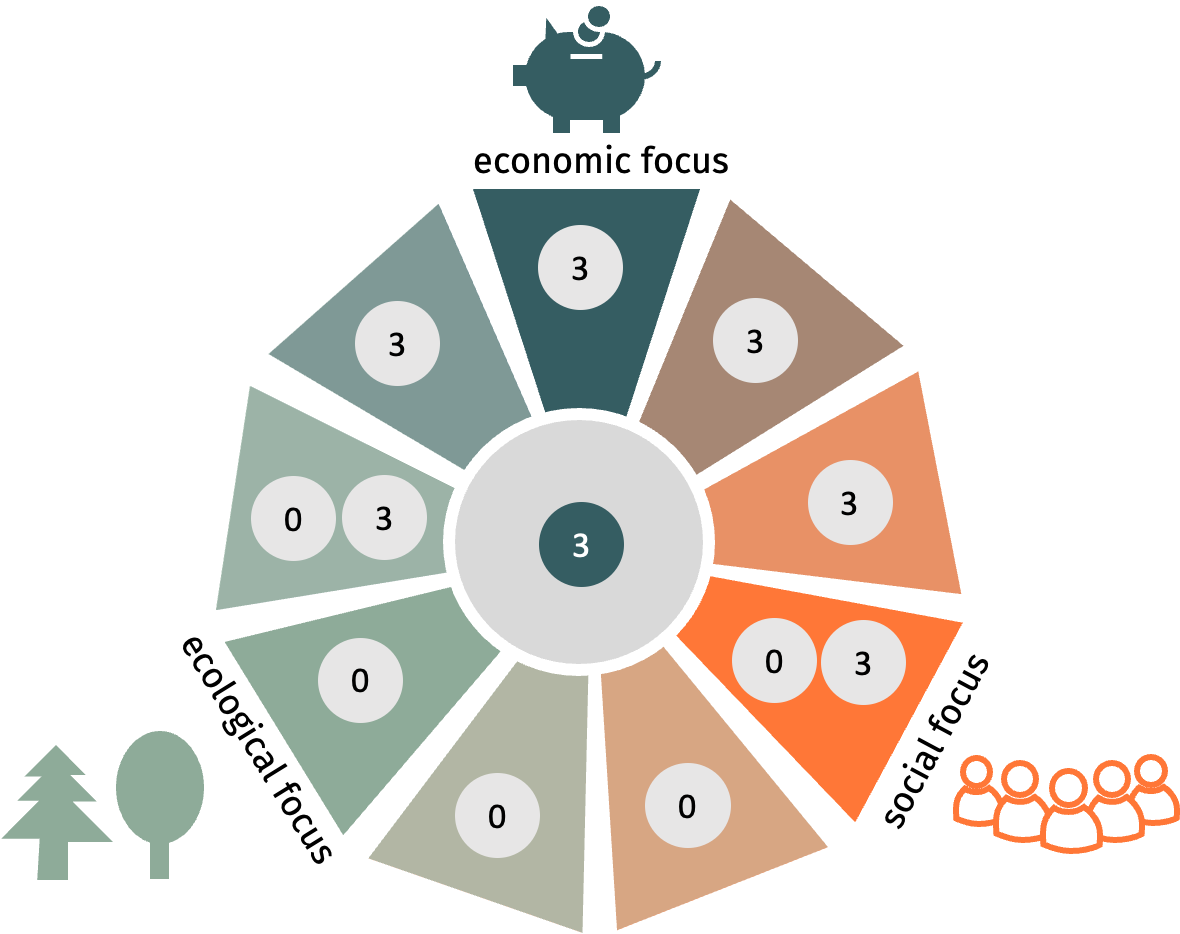

And when we combine both, efficiency and effectiveness, things become clearer:

The same basics can be used to point out the focus area of a specific option, like here the zero option that is the winer under ecological and societal view.  (See more at PR1-F05) | |

Rules and laws for forest operationsConcerning the basic concept of Technodiversity, decision making should respect local societal needs to keep a certain societal compatibility. In some cases, the local society has developed a specific sensitivity against human impacts to nature in general, and forest land in particular. In other cases, people fear that forest activities can destroy historical sites, natural monuments etc. In general, the correlations with harvesting activities are too specific for drawing general rules. When an issue arises, decision makers need to manage it individually. Very often, restrictions are explicitly formulated as laws, landscape plans or other regulations. Obviously, official regulations must be heeded to and if any such regulations concern an operation, they must be considered since the beginning at the planning stage. When selecting the most suitable system, any option going against such regulations must be immediately excluded from the list. (See more at TDiv PR1-E02) | |

RutsSee types of ruts on trails | |

Ruts by traffic on bare soilSee sectors under wheel | |